Prepared by David Luhr, Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT)

In the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) text, there is a Declaration of Policy [Title 23, Sec. 150, paragraph (a)] that states: “Performance management will transform the Federal-aid highway program and provide a means to the most efficient investment of Federal transportation funds …”. Yet, in the proposed MAP-21 pavement performance measures (Notice of Proposed Rule Making), there is no mention of pavement costs or the concept of monitoring the “efficient investment of Federal transportation funds”. This article proposes a special application of Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) as a tool in making decisions and monitoring the cost-effectiveness of pavement management.

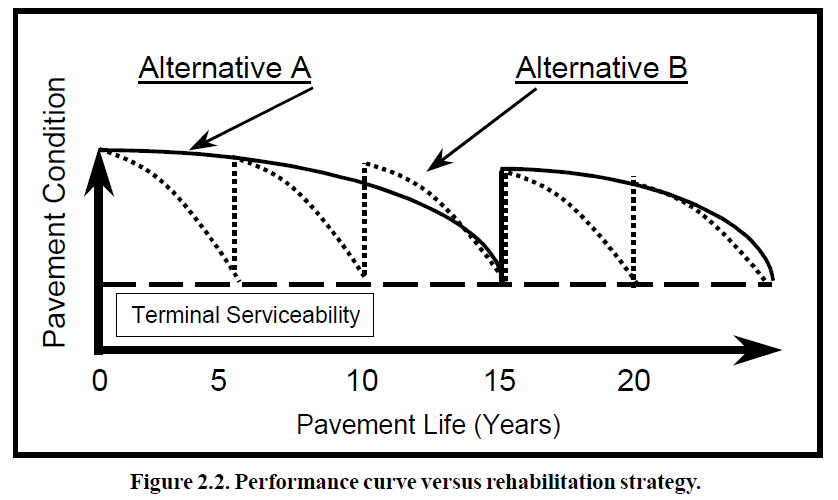

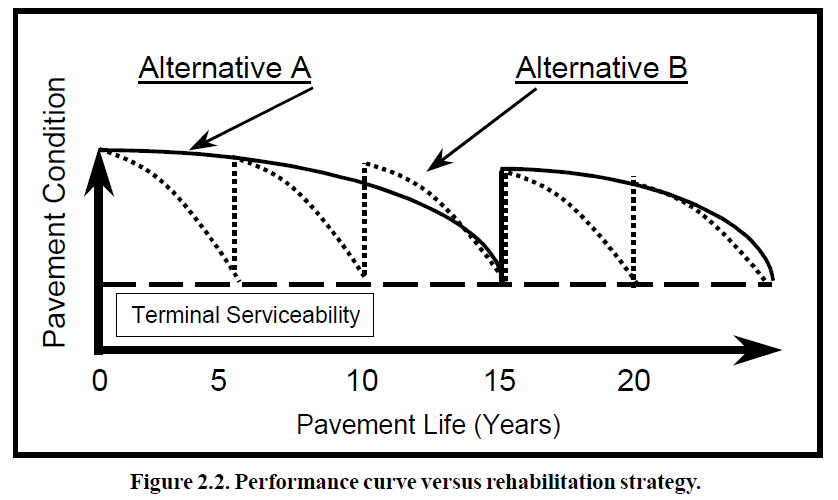

Calculating the LCCA of pavement assets has been performed since the early days of pavement management. Traditionally the LCCA has been used to evaluate different pavement design alternatives in order to select a long-term strategy. The figure below is taken from the FHWA publication titled “Life-Cycle Cost Analysis in Pavement Design” (publication FHWA-SA-98-079)

This figure illustrates the choice between two alternatives; one that is designed for long performance periods (15 years), and one that is designed for shorter periods (5 years). We would typically determine the LCCA for each alternative and use this information to select a design strategy. We can call this the Strategic LCCA.

The Strategic LCCA is estimated to make decisions for pavement type selection, and long-term pavement strategies. However, there are few new alignments being designed and built today, and reconstruction is infrequent because of a concerted effort at most agencies to preserve the pavement structure and avoid reconstruction.

A far more common situation is the year-to-year decisions that are made regarding the maintenance, preservation, and resurfacing treatments for a given section of roadway. These decisions are made based on the conditions in a specific performance period. The rate of pavement deterioration, the maintenance treatments appropriate for the pavement condition, the timing of the eventual rehabilitation, the costs incurred, are all part of a single performance period evaluation.

The actual costs incurred from construction, maintenance and preservation (we can call this the Actual LCCA) can be compared with observed pavement performance to evaluate how cost-effective the actual performance has been, and compare with the Strategic LCCA. It will turn out that the Actual LCCA will be more important than the Strategic LCCA, since the actual conditions will be used to determine the best pavement management decisions.

LCCA is typically expressed in terms of Equivalent Uniform Annual Cost (EUAC), or Net Present Value (NPV). When evaluating the cost-effectiveness of pavement management there are significant advantages to characterize the life-cycle costs in terms of EUAC rather than NPV. The NPV expresses the total cost only, but the EUAC relates cost to a period of time, which is very useful for expressing cost-effectiveness. For example,

- the EUAC is a simple value that can be directly compared with the annual cost of a different project, or with average annual costs statewide,

- the EUAC is easier to calculate, since the time periods comparing alternatives can be different (no need to use multiple performance periods to compare exactly the same number of years like NPV), and

- when using EUAC, there is no need to consider Salvage Value. In practice, pavements are not salvaged at the end of service life, but are typically rehabilitated for a new performance period.

The figure below shows the Actual EUAC over time for an example Performance Period (defined as the period of time between two pavement rehabilitation projects). As the years progress the annual costs decline as we are spreading the costs over more years. As the pavement gets older, maintenance and preservation costs increase, which can also be calculated in terms of EUAC, and added to the construction costs to get a plot of Total Annual Cost over time.

At some point in time the maintenance costs will increase to the point that the Total EUAC begins to increase. In Decision Analysis methods (specifically Replacement Analysis) the lowest point on the Actual EUAC curve is the optimum time to rehabilitate the current pavement structure. At Washington State DOT (WSDOT), we evaluate the Actual EUAC when a pavement is proposed for rehabilitation, and compare with the change in Annual Cost expected with additional preservation treatments. Often, the preservation treatment will result in a lower Annual Cost, so the pavement rehabilitation project will be delayed. The important thing to note in these evaluations is that we are using Actual EUAC, based on actual costs and observed performance for a particular segment of road. This provides us the best information to evaluate and make important decisions. Even a difference in timing of one year can make a difference. WSDOT experience has shown that a one year change in the year of resurfacing can make a 14% – 20% difference in project cost for chip seals, and 4% – 8% difference for asphalt concrete resurfacing projects.

The evaluation of the Actual EUAC (expressed as $/lane-mile/year) of pavement management decisions becomes a valuable performance management tool in answering these questions:

- How much has it cost to deliver pavement functionality on the road network?

- What are the most cost-effective pavement management practices?

- Has the investment in the pavement infrastructure been adequate for long term sustainability?

- How well are the pavement assets being managed?

Having answers to these questions is essential for pavement asset management. The costs will obviously be a factor dependent on site conditions and traffic, but for any set of site conditions an agency should have a method for tracking the cost-effectiveness of pavement management decisions.

The topic of pavement economics was further explored in a paper titled “Economic Evaluation of Pavement Management Decisions,” presented at the ICMPA9 conference. For more information, contact David Luhr at Luhrd@wsdot.wa.gov